When tradition is embraced with love, it evolves—not to erase the past, but to enrich it. Wayang World tells how wayang—Javanese shadow puppetry—crosses the boundaries of geography, religion, and time to create new atmosphere and genres. From royal romances and classical Chinese legends to Judeo-Christian stories, these contemporary interpretations are not deviations, but heartfelt continuations through the lens of acculturation and creative spirit.

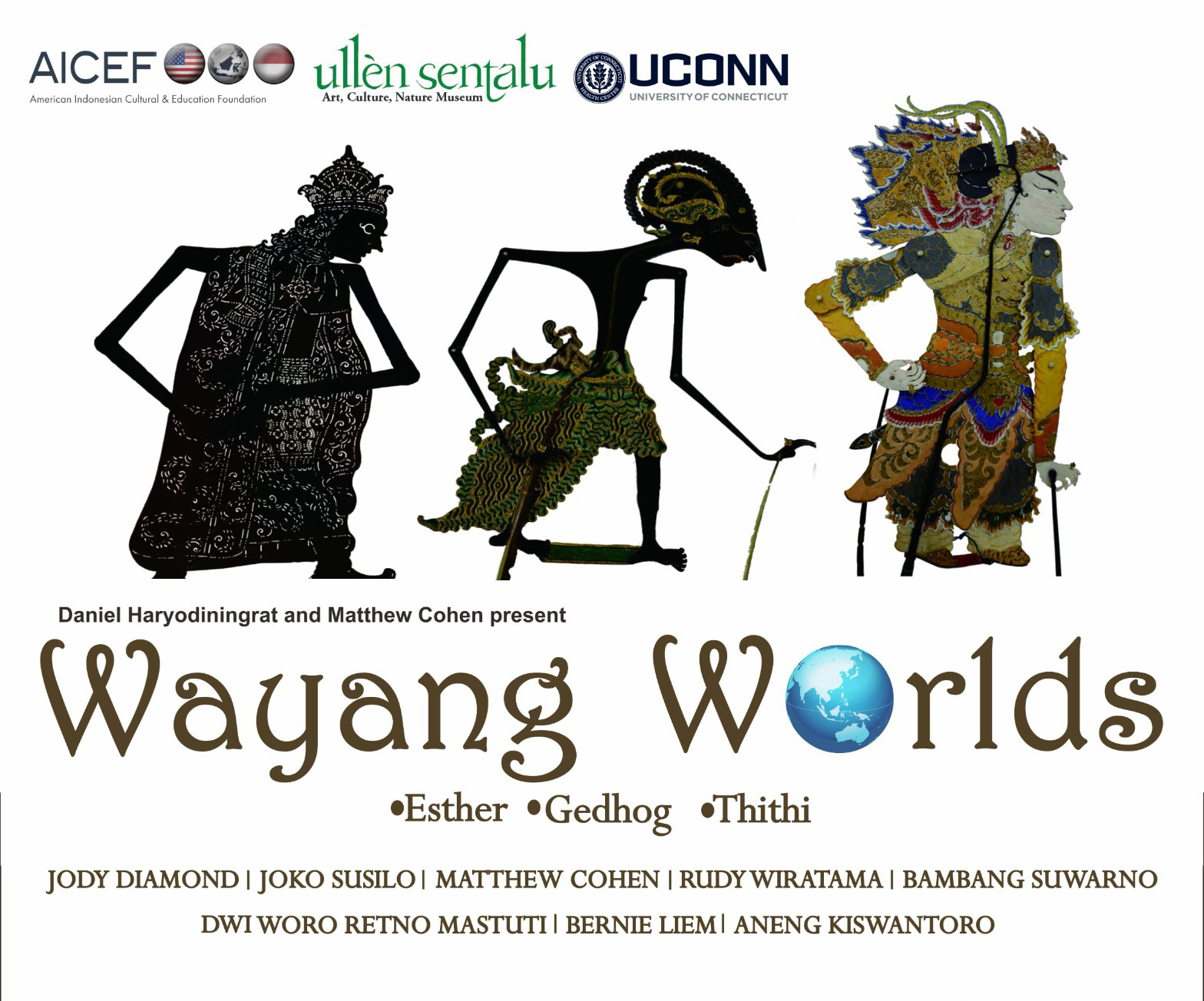

Wayang World is an event presented by Daniel Haryono and Matthew Cohen, featuring various wayang experts as speakers to discuss Wayang Esther, Gedhog, and Thithi.

Wayang World showcasing how Javanese shadow puppetry transcends cultural and temporal boundaries, from the revival Wayang Esther to innovative adaptations Wayang Gedhog and Thiti Puppetsdemonstrating that wayang remains a living form of creative expression across generations and continents.

Tradition Reimagined

Barbara Benary, a Jewish-American ethnomusicologist, was among the first to introduce a Javanese-style gamelan ensemble in the United States. Her group, Son of Lion, often blended gamelan with Jewish liturgical melodies. Although Barbara was not particularly religious, her musical and cultural sensibilities were deeply shaped by her heritage—turning belief into culture, and culture into collaboration.

From this fertile ground emerged Wayang Esthera shadow puppet performance based on the biblical story of Queen Esther.

The performance was first staged in 1999 and revived several years later when composer Matthew Cohen reached out to Javanese puppeteer Joko Susilo and composer Jody Diamond to bring it back. The plan was to restage it for Purim, a Jewish holiday, in West Hartford, Connecticut. However, reconstructing the performance was no easy task—music scores had to be located, puppets redesigned, and everything reassembled from memory.

Joko, who initially used traditional wayang Purwa, had to design new characters tailored to the Esther narrative. “At first, they looked too Javanese,” he recalled. “The noses weren’t quite right.” This process became a long, transcontinental journey of revisions and refinements. Meanwhile, Matthew introduced historical visuals: an illustrated Book of Esther from 18th-century Italy. Although not originally made for puppetry, the proportions of the characters resembled wayang figures. With Joko’s designs and Matthew’s visual sources, the team created a two-layered performance—one using puppets, the other with projections—allowing the audience to experience both tradition and reinterpretation simultaneously.

Reviving the Panji Romance

In Indonesia, another form of revival was also underway. For the anniversary of the Radya Pustaka Museum in Surakarta, puppeteer and researcher Rudy Wiratama proposed staging Wayang Gedhog, a lesser-known form of wayang based on the romantic tales of Prince Panji. He selected the story Ngrenaswaraa rarely performed sequel to Panji Anggraeni the better-known one. “It completes the story with a happy ending,” Rudi explained. By compressing several acts into a single evening, the team created a three-hour version that remained faithful to the emotional arc, even if not to every word of the original text.

For Rudy, Wayang Gedhog holds enormous creative potential—not only in courtly versions, but also from poetic sources such as kidung from 16th- and 17th-century Java. “This is a door that remains wide open,” he said. The same spirit of innovation can be heard in the work of Bambang Suwarno, who in the 1970s created his own Panji puppets independently of the Kraton tradition. Combining puppetry with topeng, he used a distinctive green palette—pare anom—and created kayon a custom kayon (tree of life) called Sekar Jagad, which combined images of fire, flora, and fauna, making the visual design itself a performance of symbolism.

Chinese-Javanese Echoes

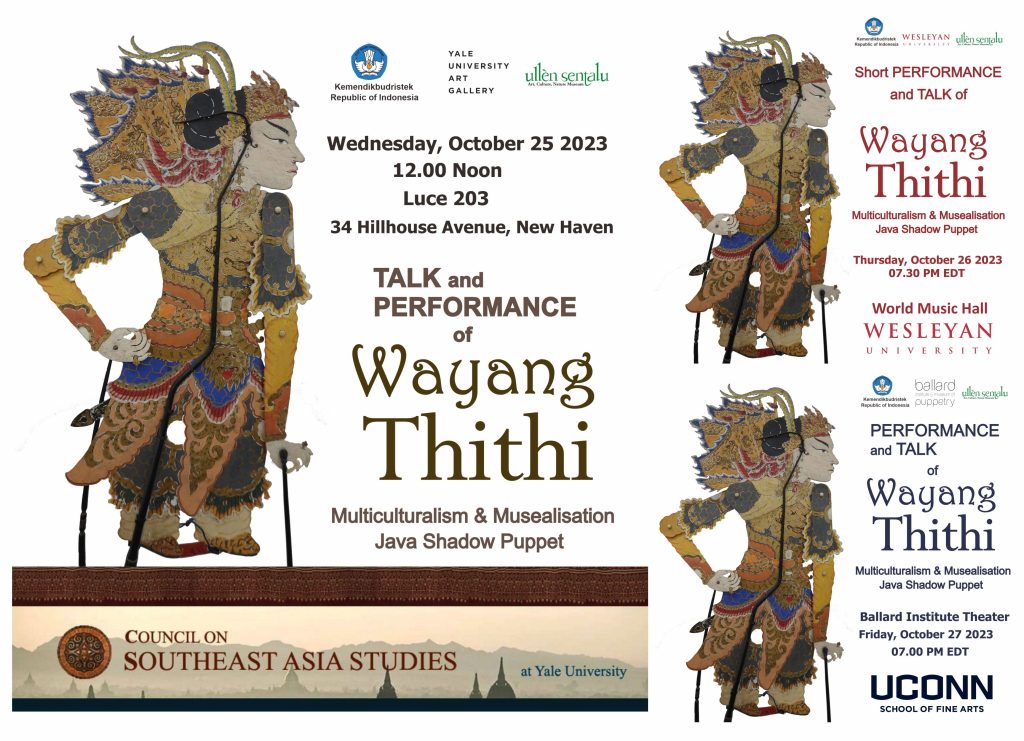

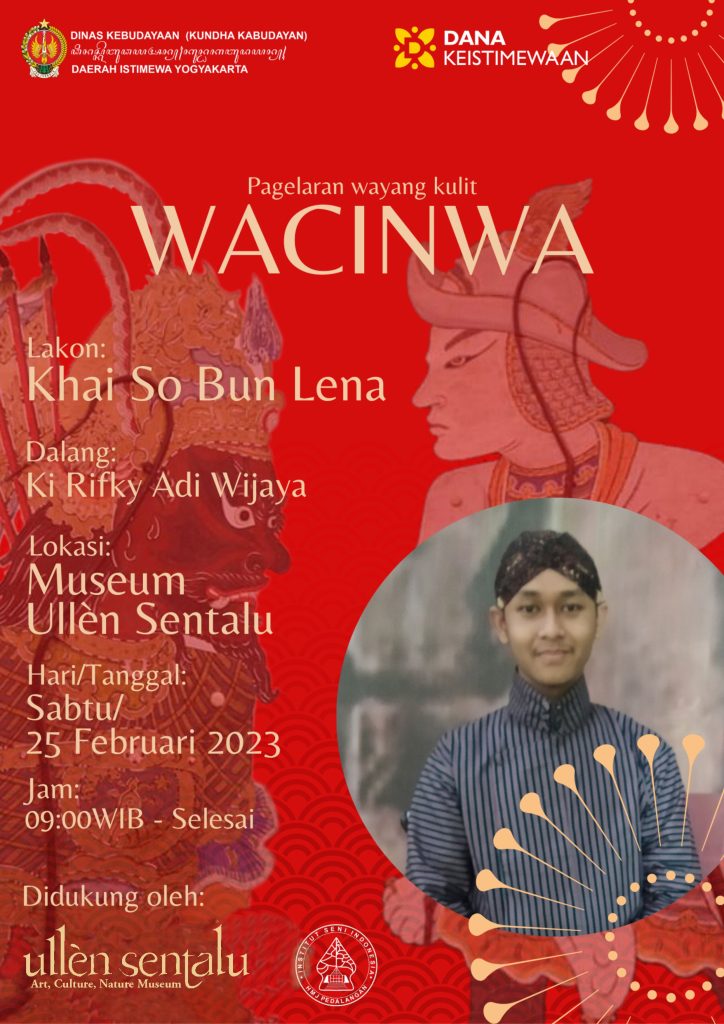

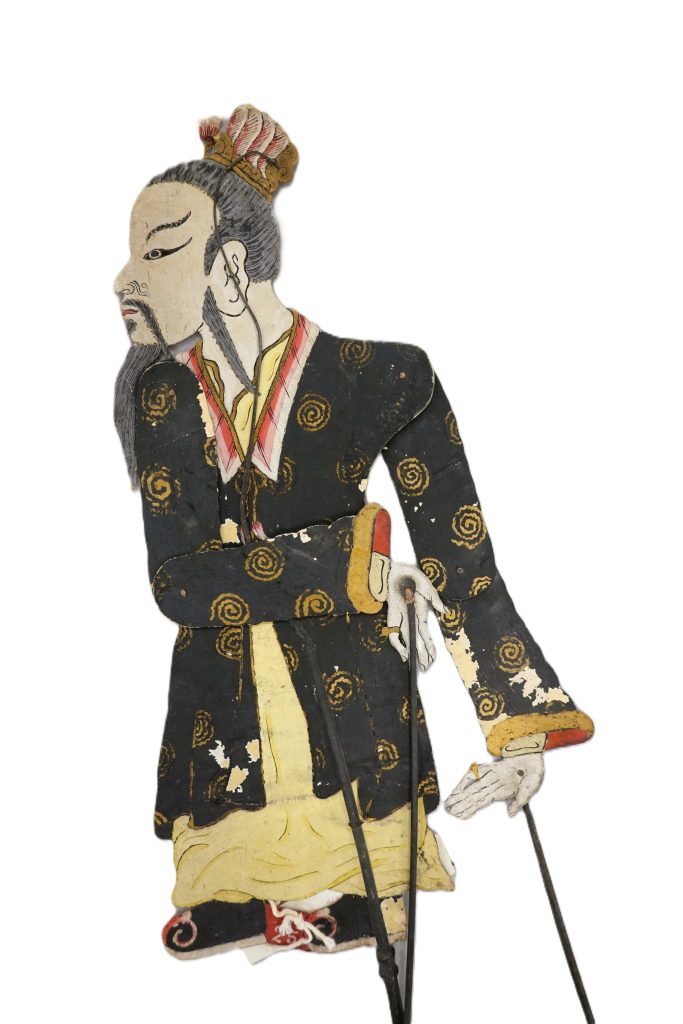

Wayang also thrives in the cultural dialogue between Java and China. In Yogyakarta, Chinese-Indonesian artist Gan Thwan Sing introduced Thiti Puppets, later known as Wacinwa (Wayang Kulit Cina Jawa). He adapted Chinese legends such as the story of Sie Jin Kui, but narrated them in Javanese. The result was a performance that felt both local and transnational—easy to follow, rich in visual detail, and deeply loved by its audience.

Gan’s legacy was later continued by Woro, an artist and researcher who rediscovered 19 Chinese-Javanese manuscripts that had remained untouched for decades. “When I found them, it felt like a treasure hunt,” she said. These texts used Chinese names transliterated into Javanese script with vocal markers—puzzling even for students of Chinese studies. The language, like the puppets themselves, had been hybridized. “These are Hok Kian names, Javanized,” Woro explained. “No one knew how to read them, not even my lecturers.”

In 2014, puppeteer Aneng staged Wacinwa based on a comic-style narrative of Sie Jin Kui’s first encounter with his wife. However, practical challenges arose—no puppets were available for the performance, and borrowing from the museum proved impossible. So Aneng built his own, taller and more functional for stage use, yet still true to the spirit of Gan Thwan Sing’s originals. “You can’t always wait for institutions to approve,” he said. “Sometimes, you have to create your own tradition.”

Wayang Lives On

Across continents and centuries, these evolving forms of wayang prove one thing: wayang is not a relic of the past, but a living, breathing language of expression. From synagogues in New York to museum halls in Surakarta, from palace archives to forgotten manuscripts, wayang continues to find new stories and new audiences. As Woro puts it, “If we give life to wayang, it will give life to us. Wayang never dies.”

Wayang makes the world go round.

GALLERY

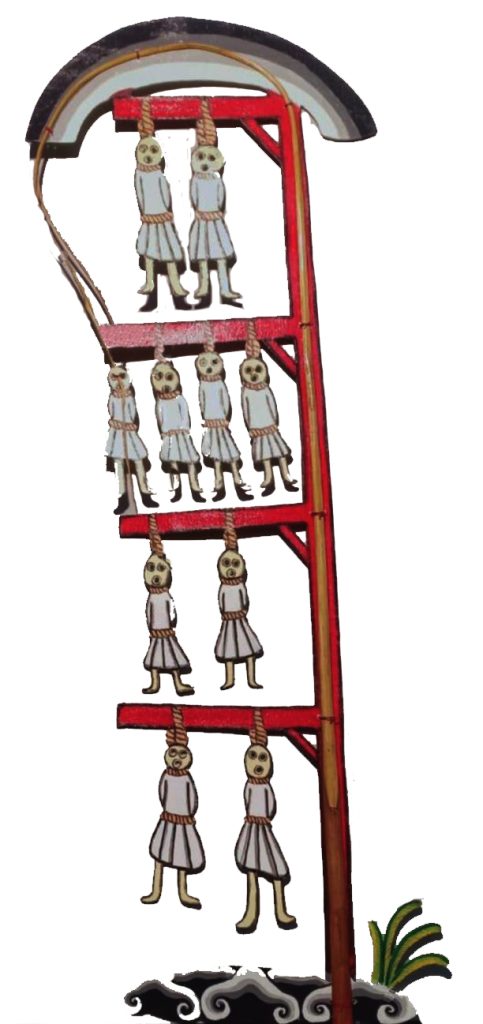

Wayang Gedhog

Thiti Puppets

Wayang Esther