Wayang kulit purwa is not merely a shadow performance behind the screen, but a work of visual art that fuses meaning, technique, and emotion. In the hands of Yogyakarta’s masters and princes, wayang becomes a symbol of refined character and clear aesthetic sensibility. Every carving, color, and movement holds a story about the taste of Javanese nobility, who expressed their love of art through forms rich with meaning.

Adapted from “Variants and Diversity of Yogyakarta-Style Purwa Leather Puppets in Documentation and Character Analysis: A Brief Review of Puppet Visual Art,” by R Bima Slamet Raharja.

This writing traces the beauty and diversity of the Yogyakarta-style wayang kulit purwa from three princely collections—Hangabehi, Mangkukusuma, and Ngabeyan. Each reflects the refinement of craftsmanship, philosophy, and Javanese creativity, affirming that wayang is not merely a performing art, but a living heritage that intertwines aesthetics, spirituality, and cultural identity.

As Soedarso Sp noted, wayang kulit belongs to the realm of seni kriya (craft art), which is not only beautiful but also functional—serving as a medium to visualize tales of heroism and life philosophy. In Yogyakarta’s tradition, wayang evolved within a cultural sphere known as adiluhung —a pinnacle of refined taste and craftsmanship passed down through generations.

From this royal milieu emerged various princely variants of wayang, each reflecting the personality, taste, and spirit of its era. Three of them—the creations of Prince Hangabehi, Prince Mangkukusuma, and Prince Hangabehi of Ngabeyan—stand as living witnesses to how wayang evolved from tradition into a deeply personal expression of beauty.

Hangabehi Wayang: Refined Elegance in Gold

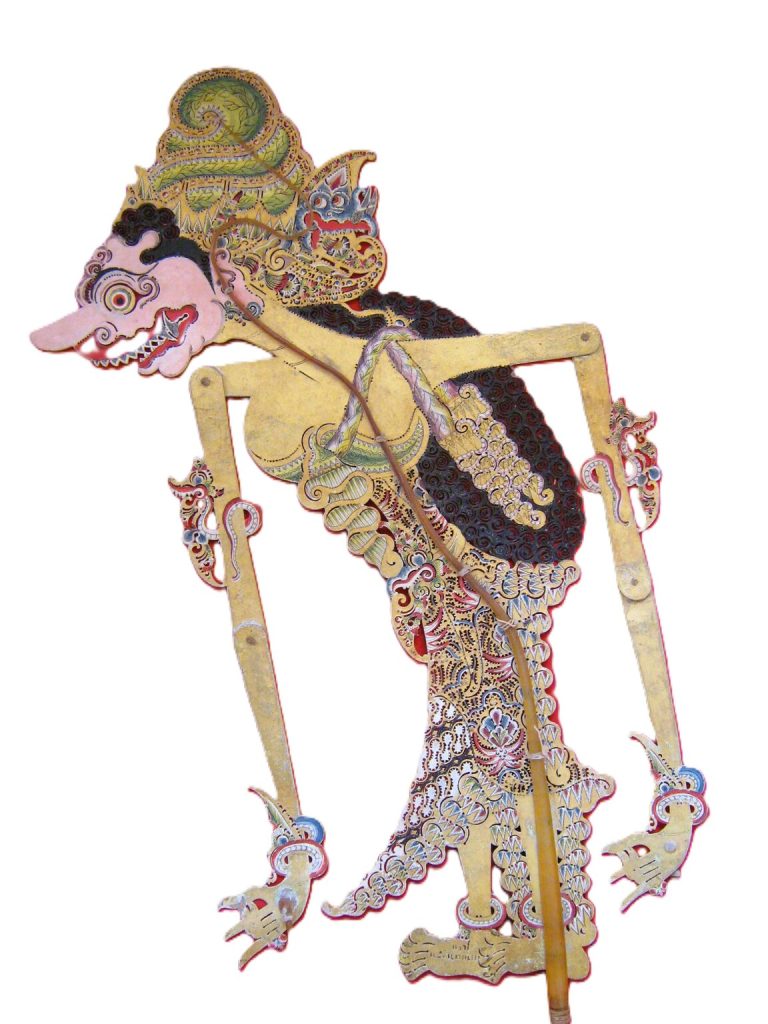

Collection of Kangjeng Gusti Pangeran Adipati Hangabehi—the eldest son of Sultan Hamengku Buwana VII—now resides in the collection of RRI (National Broadcasting Station) in Yogyakarta. This ensemble is among the most complete and exquisite in the history of Yogyakarta wayang. Every element—from the puppets to the screen and gamelan—was crafted in harmony, reflecting a unified aesthetic vision and meticulous design.

The distinctive feature of the Hangabehi wayang lies in its carvings, which are ngrawit, fine and intricate, dominated by the motif inten-intenan with color embellished with gold leaf (prada emas). The chosen colors are not merely decorative but carry symbolic meanings tied to each character. A red face, for instance, represents courage and anger, while black symbolizes calmness and wisdom.

The beauty of this collection also shines through its costume motifs. The cloth kampuh of the wayang figures features a variety of classic batik patterns such as parang, kawung, and semen, while the lower garments are adorned with the cindhe motif, cindhe which is a hallmark of the Yogyakarta style. Prince Hangabehi granted his penyungging (painters) the freedom to explore their creativity, resulting in figures that feel vibrant and full of character rather than repetitive.

On the puppet’s feet, a carved Javanese inscription reads “Ka Pa Ha Ha(ng)” — an abbreviation of the prince’s name — accompanied by the year of creation: 1842 in the Javanese calendar, or 1916 CE. This small detail serves both as a historical marker and as the aesthetic signature of a true connoisseur of art.

Mangkukusuman Wayang: Grace in Simplicity

Meanwhile, puppets of yasan Gusti Pangeran Harya Mangkukusuma, the son of Sultan Hamengku Buwana VII from his consort Kangjeng Ratu Kencana, had a different character. This collection was once scattered in various places, one of which was the late Moheni’s house in Bantul. Although no longer complete, its beauty and uniqueness can still be appreciated.

Prince Mangkukusuma entrusted the creation of the wayang to two renowned craftsmen, Ki Kertiwanda and Ki Prawirasucitra. The Kertiwanda style is easily recognized by the wayang’s wide eyes, straightforward yet graceful detailing, and the use of motifs kawatan — a carved pattern resembling waves filled with floral motifs. Unlike the Hangabehi puppets, which are rich in gold ornamentation, the Mangkukusuman style highlights an elegant simplicity.

The coloring technique, or sunggingan on this wayang often employs soft gradients without additional ornamentation (bludiran). The colors are layered, three to six levels deep, creating a calm and profound impression. On the hands, the skin tone matches the face, as if the character is wearing gloves—a distinctive style of the 1800s.

Another interesting aspect is the appearance of characters from pawukon, the ancient Javanese calendar system, such as Watugunung and Wukir. This reflects the prince’s effort to broaden the scope of wayang stories, drawing not only from the Mahabharata or Ramayana epics but also from local cosmology and philosophy.

Wayang Ngabeyan: Innovation Amid Tradition

The third variant comes from Kangjeng Gusti Pangeran Harya Hangabehi, the son of Sultan Hamengku Buwana VIII. He is known as Wayang Ngabeyan, this collection has now become an asset of the Special Region of Yogyakarta and is kept in the Bangsal Kepatihan. With more than 600 figures, these wayang are among the largest and most complex collections.

Prince Hangabehi was known as a contemplative artist. He not only collected wayang but also created new characters. In the story of Pringgandani, for example, he reinterpreted Gatotkaca’s uncles—Brajamusthi, Brajadhenta, Brajawikalpa, and Brajalamatan—giving them more heroic and energetic traits. He also created figures from the story of Lokapala and Arjunasasrabahu which were previously little known to the public.

The main characteristic of Wayang Ngabeyan is the dominance of gold (brongsong) and very delicate detailing. The motifs inten-intenan dominate the ear decorations (sumping) and the crown (makutha), while the clothing displays patterns parang klithik and cindhe. Not only focusing on human characters, Prince Hangabehi also paid attention to the details of animals and nature. Dhudhahan wayang, such as trees, dragons, and fish, were depicted in a realistic style resembling paintings—a feature rarely seen in later eras.

Interestingly, each wayang was marked with the code “Pa Ha” (Prince Hangabehi) and its creation date. This collection was made between the 1930s and 1960s, making it younger than the two previous variants, yet it still exudes the elegance of the classical style.

Preserving the Soul in Shadows

These three princely wayang collections demonstrate how Javanese craft art evolved within a cultural environment rich in emotion and meaning. Each prince expressed his worldview through the shapes, colors, and proportions of the figures. From the subtlety ngrawit From Hangabehi and the meditative simplicity of Mangkukusuma to the creative innovations of Ngabeyan — all of them record the journey of Javanese aesthetics across the ages.

More than mere objects, wayang serve as mirrors of the spirit of their era. They record philosophical values such as sawiji, greget, sengguh, ora mingkuh —the guiding principles of Yogyakarta society, emphasizing a balance between earnestness and serenity.

Delving into wayang means immersing oneself in the Javanese worldview: that beauty is not only about appearance, but also about attitude, patience, and wisdom. Behind each carefully carved leather figure lies a prayer that humans remain aware—mindful of their origins and aware of the harmony between the world, art, and spirituality.

Gallery

Here are several examples of Wayang Purwa from the RRI Yogyakarta collection. For high-resolution images and complete documentation of Wayang Gedhog, please contact us.